Part 2 Indian

-

01 08

Background

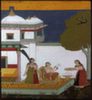

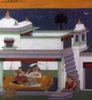

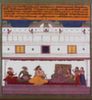

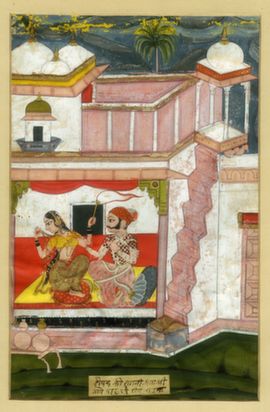

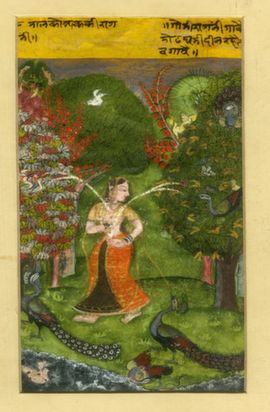

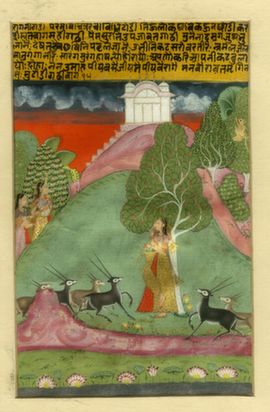

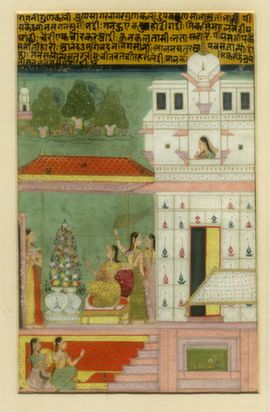

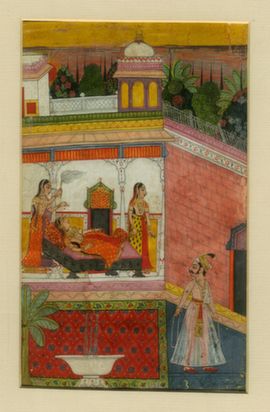

Development of the Classical Form and the System of Ragamala Composition

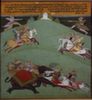

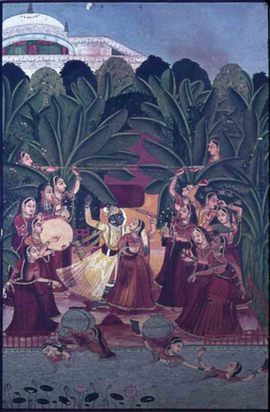

The great diversity of musical types in India reflects racial, linguistic and cultural variance. At the same time, it has a great functional character and continues as one of the sustaining components of sacred ceremonies and secular festivities. Ancient Indian scriptures refer to the origin of music as a divine phenomenon; all the three deities of Hindu triade, Brahma, Vishnu and Siva, being the primordial musicians. The 'divine beginnings' of the music was systematized over the centuries and as laid down in the Sanskrit canons, the classical form had melody (raga) and rhythm (tala) as vital constituents.

The use of drone is a fundamental element of the classical music, usually provided by a wind instrument or a plucked stringed instrument, tuned to a pitch suited to the principal performer. The classical melodic forms were presented usually accompanied by a melody instrument set to the principal melody line and one or more percussion instruments to mark the time measure and act as the rhythmic counterpoint.

- 02 08

The Nature of a Raga

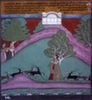

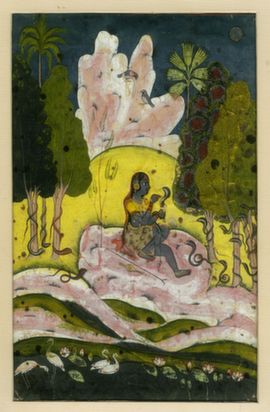

The conception of ragas and raginis are the basic principles of Indian music and they have no exact parallel in any other musical tradition. The nature of a raga, a melody-mould or musical pattern, as has been defined by Matanga (c.10th Century CE), the ancient authority, in his seminal treatise, Brihaddesi, is as follows: "A raga is identified by the enlightened ones as a kind of sound composition adorned with musical notes in some peculiarly stationary (sthayi), or ascending (arohana), or moving (sanchari) values (varna), which have the effect of colouring the hearts of men". In its literary connotation a raga would mean "something that colours, or tinges the mind" with some definite feeling, an influx of passion, or emotion. The "colouring" caused by a raga is certainly associated to a certain spatio-temporal context and is bound to differ.

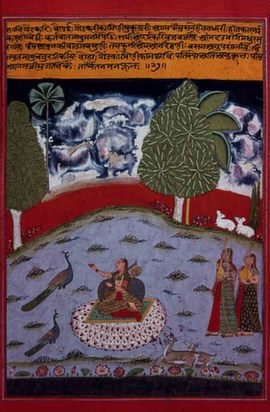

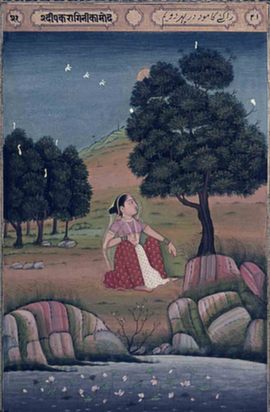

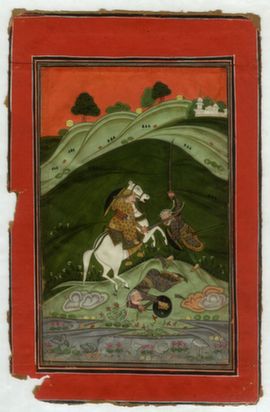

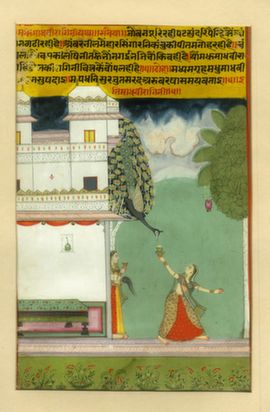

Every raga has its special sequence of ascending notes (aroha) and descending notes (avaroha) that determine its structure or that (lit. an array or setting). A raga experience would change from dawn to dusk, from a sunny afternoon to a moonlit night, from spring to autumn, so on and so forth. On the basis of this, ragas and raginis were associated with particular moods and regions, with particular seasons and, categorically, to the explicit hours of the day and night. For example Dipaka raga was associated with fire and scorching heat while the recital of Megha raga, in contrast, was ideal for the season of clouds and rains, its flawless rendition promising downpour. Similarly, Vasanta raga is meant to express the joy of life in spring and Nata raga, the heroic martial spirit of the man. Bhairavi ragini is the plaintive melody of the morning and raga Yaman is meant to evoke the somber, explicitly devotional mood in the early hours of the evening. However, a raga is not a song or tune, on the other hand numberless songs can be composed in a certain raga-mould (for more on Ragas go to Raga in Context).

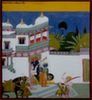

Bharata in his Natyashastra (c.2nd century C.E.), a celebrated work dealing with dramaturgy in all its aspects, made a reference to grama-ragas as certain musical entities to be performed as a part of the enactment of Sanskrit classical drama. The Kudumiyamalai inscription of c. 7th century C.E. on a flat rocky surface in the old native state of Pudukkottai in Tamilnadu, describe seven grama-ragas. Spread over an area of approximately sixteen square meteres, this seminal inscription commissioned by the art-loving Pallava kings serves as a meaningful link between the Natyashastra and the subsequent textual references regarding the raga classification. Matanga was the first to discuss the raga categorization in detail. Next important text to focus on the subject was Sangita-Ratnakara. Sarangadeva, a scholar with a passion for music, hailed originally from Kashmir and during his stay at Devagiri (Daultabad) in Deccan between 1210 and 1247 C.E. completed this encyclopaedic work. He presented a survey of ragas according to his fore-runners including Matanga.

-

03 08

Systems of

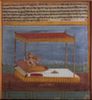

Ragamala

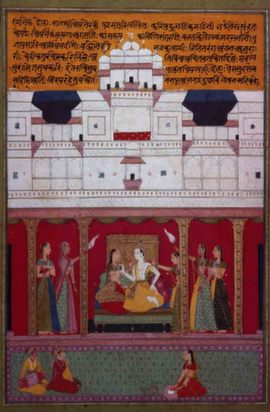

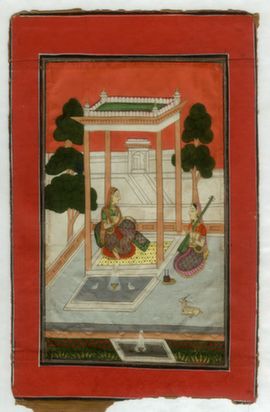

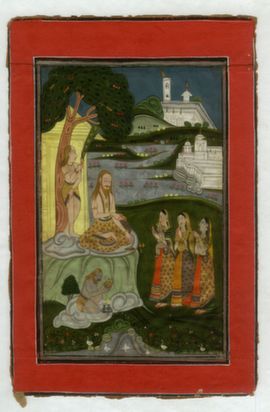

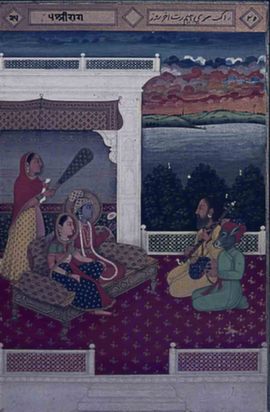

CompositionsWith a view to emphasize the divine qualities of music, each raga and ragini was attributed with a particular rupa or psychic form. The psychic form was further divided into the invisible sound form or the nadamaya rupa and tangible or image form referred to as devatamaya rupa. It was required on the part of a performer (kalavanta) to imbibe the presiding spirit or ethos of a melody and please the deified form. Raga-dhyanas or contemplative prayer-formulas were devised for the purpose, passed on from the master (acharya, ustad) to the student.

A melodic rendition cannot be successful without a proper invocation of the deified form and any amount of mastery over the musical structure would not ensure the attainment of the divine essence inherent in every raga. Sri Kantha in his Rasa-Kaumudi (c.1575 C.E.) laid down the injunction that "those unskillful singers who attempt to interpret any melody without following the image given in the contemplative verse (dhyana), can never achieve the spiritual values (phala) prescribed in the science of music (sangita shastra)".

Being an important segment of music-lore, the raga-ragini iconographies as enjoined in the descriptive dhyana verses were once carefully studied by all practitioners of Indian music. The raga-dhyana verses were available in Sanskrit, Brajabhasha and even in Persian. The visual illustrations in the form of ragamala paintings followed the raga-dhyanas in order to portray the or the emotive essence of a particular melody.

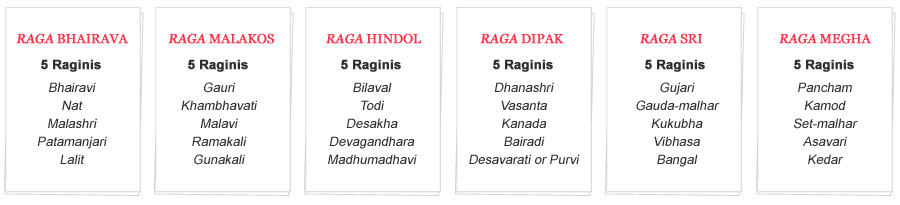

In Narada's Sangita Makaranda, datable between 7th and 11th century C.E., do we come across for the first time a classification system of six ragas as male and six raginis, attached to each raga, as females forming six cohesive families, raga-parivara. However, this system was not followed by the painters. It is in the Sangita Makaranda that we find for the first time a classification of ragas according to the proper hour for rendition. Mesakarna or Kshema Karna, a sixteenth-century rhetorician from Rewa (central India), in his treatise Ragamala compiled the elaborate system of six ragas, each with five raginis and eight ragaputras. This system of ragamala composition belongs to the period before the revival of Indian music under Akbar, renowned for his musical acumen and catholicity of artistic taste. It had been followed in a restricted manner with some changes by the painters of Rajasthan and Deccan, but in the ragamala sets belonging to the Pahari tradition this system was adopted all along.

-

04 08

Mesakarna or Kshema Karna's

System of Compositional Pattern

The system of building up a compositional pattern of melodies as stated in his remarkable text Ragamala (one manuscript with a colophon dated 1509 C.E.) is quoted below:

-

05 08

Hanumana's System

of Ragamala Composition

Some of the earliest raga-dhyanas (contemplative prayer-formulas) inscribed on the surviving specimens of ragamala paintings are credited to the ancient theoretician, Hanumana, who may have lived between 5th and 12th centuries. Regarded as one of the commentators of Bharata's Natyashastra, he propounded a system of six ragas with five raginis each. His ragamala composition is as follows:

-

06 08

Klaus Ebeling's

"Painters' System"

The exhaustive research incorporating both, the in-depth study of ragamala miniatures and musical texts, led Klaus Ebeling to conclude with a "Painters' System". He could locate in approximately two thousand inscribed paintings the continuity of this particular mode of an obscure origin. The "Painters' System" in its detailed breakdown as documented by Ebeling is as follows:

-

08 08

Wide range of media to explore

The Ragamala digital experience has been crafted to deliver a rich experience to the users across a wide array of media ranging from images to sound:

You are currently viewing:

Part 2: Indian Music | Development of the classical form and system of Ragamala Composition.

View Part 3: Indian Painting