Part 3 Indian

-

01 07

Early Traditions

Indian Miniature Painting Overview

Anecdotes from the ageless lyric tradition of India refer to small format paintings (anu-chitra), invariably portraits of princess and courtesans, that acted as catalysts in romance and clandestine love affair. Incidentally, the earliest surviving miniatures, unearthed from the ancient capital of India's first empire, represent this secular genre once patronized by the cultured city-based elite. These little known tiny artefacts bear an unmistakable Hellenistic expressive subtlety. Those were painted in deep red-ochre on fragile mica sheets, circular in shape and are datable to c.150 B.C.

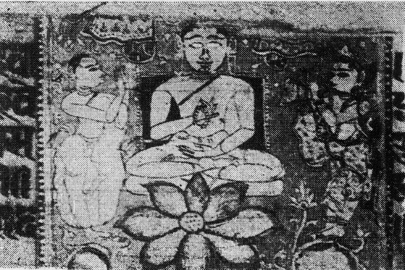

Successive examples of 11th – 13th century are the illuminated palm-leaf manuscripts and painted wooden manuscript-covers executed in the Mahayana Buddhist monastic guilds of eastern India and Bihar. In the rendition of the complex iconographic details of the cult images set in small compartments of the oblong palm leaves, the painters strictly adhered to the canonical rubrics laid down in the esoteric ritual texts. Depiction of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and a plethora of Vajrayana deities as also miraculous events from the life of Gautama Buddha were meant to enhance the spiritual efficacy of the sacred manuscripts and protect the owner from physical as well as supernatural harm. The suave linear rhythm and plasticity of the painted icons display an unmistakable linkage to the world-renowned wall paintings of the cave sanctuaries at Ajanta and Bagh.

Early Traditions Continued

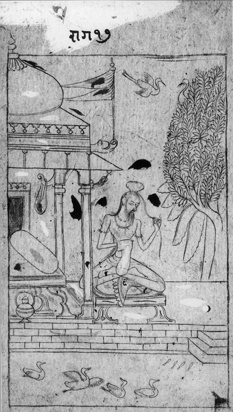

A parallel tradition flourished between 11th and 16th centuries in the Jaina temple scriptoria of Western India, mainly Gujarat and Rajasthan. Restricted initially to the illumination of the two cardinal texts of Jainism, viz. Kalpasutra and Kalakacharya katha, the idiom took a delightful turn in the narrative-inspired paintings of Jaina hagiography. The early examples are those done on palm-leaves and birch-bark. Wooden manuscript covers or patalis were embellished either with ornamental motifs or with narrative episodes. From the 14th century onwards paper became the most suitable support. The dimension of the folios was expanded that in turn provided a bigger format for the painters. The style of the paintings was rooted in a terse linearization of form, both figural and non-figural, enhanced with a strong colouristic patterning. Faces were drawn either in profile or in three-quarter profile with a long nose and pointedly oval eyes. One further eye protruding beyond the cheek became a mannerism that was, however, borrowed from the 9th century wall paintings of Ellora.

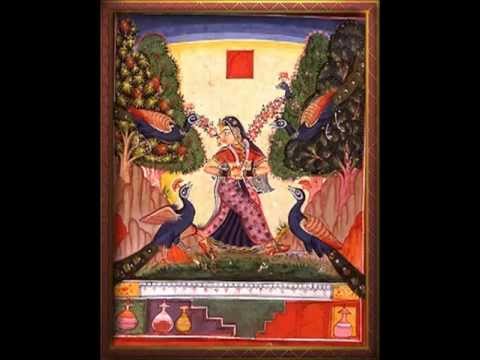

In general, the painters' palette consisted of golden yellow, rich vermilion and crimson, lapiz lazuli and terreverte, lamp-black and white. Fourteenth century onwards, the use of gold and silver made the sacred Jain manuscripts acquire an extravagant character. This "opulent style" was indeed influenced by the contemporary illustrated Islamic manuscripts in the collection of nobles in Gujarat to which some of the painters had a rare access. A large number of professional artists were engaged in the art of the book besides a limited number of monks who did also excel as gifted illuminators hence the style of the painting spread over a larger context defying the sectarian limits. As a result, many of the Hindu texts and secular romances were illustrated in the similar style, invariably in a less-rigid manner and with a stress on the expressive use of colour. On the back of a Kalpasutra illustrated in the "opulent style" and datable to c.1475 do we find the representations of the "image form" of musical modes. These forty-two "image forms" of the ragas are the earliest surviving ragamala miniatures.

-

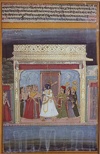

Mallari, Parsva's birth

Mallari, Parsva's birth -

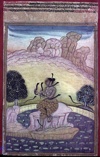

Sindhu Mallari, Mahavira as a Siddha

Sindhu Mallari, Mahavira as a Siddha -

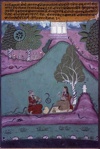

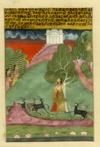

Nattanarayana, Two scenes: 1) Mahavira gives away half his garment. 2) Mahavira plucks out his hair.

Nattanarayana, Two scenes: 1) Mahavira gives away half his garment. 2) Mahavira plucks out his hair. -

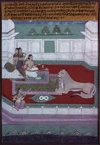

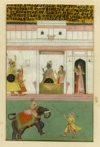

Kamoda, Mahavira in the intiation palanquin

Kamoda, Mahavira in the intiation palanquin -

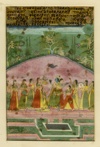

Madhuri, Mahavira gives away his possessions

Madhuri, Mahavira gives away his possessions -

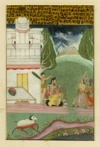

Bengali, Siddhartha celebrating the festival of Mahavira's birth

Bengali, Siddhartha celebrating the festival of Mahavira's birth

A fairly good number of illustrated manuscripts of Hindu and Islamic themes belong to the Sultanate era (14th – early 16th century C.E.). Some of these were executed at the court atelier of the provincial kingdoms whereas majority of the surviving specimens were produced for the less-exalted patrons. The patronage of aesthete-bibliophiles caused an intermingling of indigenous and Iranian pictorial idioms that eventually culminated in a series of painting styles, overtly symbolic and essentially non-naturalistic. In a phase of cultural osmosis Indian artists were quick to absorb elements from the style of migrant Iranian masters and this in turn helped them to enrich their narrative-inspired evocative visual metaphors. Spreading beyond the geographical limits of Gujarat and Rajasthan, the style found regional manifestation at Mandu and Gwalior (Central India), Agra, Palam, Jaunpur and Jai Singh Dev Nagar (near Kangra, Himachal Pradesh). There is a charming series of ragamala paintings (c.1525-70 CE) that belonging to this stylistic group. Further, the set was once lying in the collection of a Jain monk.

-

-

02 07

The Earliest

Surviving Ragamala

Paintings of C.1475 C.E.Indian Miniature Painting Overview

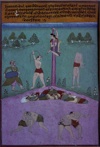

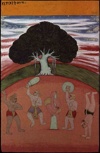

The depiction of six multi-armed male deities, labeled as raga, and thirty-six female figures as ragini on the back of twelve Kalpasutra folios are the earliest known ragamala paintings that survived. They are datable to c.1475 C.E. on stylistic ground and were formerly in the collection of the late Jaina Acharya Jaya-simha Suriji of Ahmedabad. The system followed in this ragamala series of forty-two paintings correspond to a certain degree to the raga classification system of the rhetorician Kallinatha (1460 C.E.), the famous commentator of the musical treatise Sangita-ratnakara. These small little paintings are dominated by the anthropomorphic presence of the melodic form, pessonified as gods and geniuses. The raginis are referred to as bhasa and they look like the celestial dancers painted on the margins of several other fifteenth-century Kalpasutras from Gujarat, finished with opulent details in gold and scintillating hues.

In terms of ragamala iconography, these paintings acquire a unique position. No second Kalpasutra manuscript with such ragamala paintings are known. Also, the six ragas namely, Sri, Vasanta, Bhairava, Pancham, Megha and Nata Narayana, as a group never preside any ragamala system. Similary, many of the raginis were never mentioned in the later raga-ragini classification.

The next surviving examples from Uttar Pradesh or Palam (Delhi), datable to C.1540-70 C.E. , adhere to an iconographic system that eventually became the "mainstream of the Rajasthani tradition". This important ragamala set is presently in the J.P. Goenka Collection, Kolkatta. Couplets in Braja-bhasha, a Hindi dialect of the Agra region, were inscribed on the back of the paintings. This ragamala classification system of obscure origin was followed by the Rajasthani painters of the 17th, 18th and early 19th century. A set of 36 paintings includes the depiction of 6 ragas and their 5 raginis. This ragamala iconographic tradition had aptly been referred to by Klaus Ebeling, one of the eminent scholars to interpret and analyze thoroughly the mystique of ragamala painting, as "Painters' system". Deccani painters also followed this system with certain variation.

- 03 07

Mughal Schools

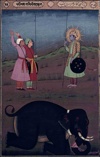

A series of remarkable monarchs, themselves aesthetes with keen understanding of literature and music, of the Mughal empire (1526-1858) caused the very inception and nurtured the crystallization of a unique form of miniature painting in their ateliers (tasvirkhana, surat-khana). The character of the pre-Mughal painting tradition of north India was altered to a considerable degree under the influence of the innovativeness of the imperial studio. The process was slow yet steady. An entire range of painted visuals of the era lead one to a memorable experience of the courtly glories of the grand Mughals. Akbar (r.1556-1605), greatest of the Mughal rulers, had lessons in painting and calligraphy during his childhood and was an ardent believer in cultural and religious synthesis. His undying passion for illustrated texts, ranging from adventure stories to ethical tales and from biographies to Persian translations of cardinal Hindu myths, necessitated an expansion of the workshop. More than hundred painters (musavvar, chitera) were recruited from Gujarat, Rajasthan, central India and Kashmir.

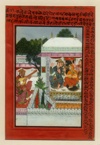

Two master painters, Ustad Mir Sayyid Ali of Tabrez and Ustad Abdus-Sammad of Shiraz, supervised the collective execution of the painters ensuring the quality production. These two masters were formerly in the court atelier of the Safavid ruler Shah Tahmasp II and migrated to India in response to the invitation extended by Akbar's father, Humayun. As was inevitable, there took place a synthesis of the lyrical Safavid idiom and intensely expressive pre-Mughal styles. From 1580 onwards, inflow of European engravings and painted tapestries opened a set of altogether different visual vocabulary. Painters were encouraged to imbibe certain traits of naturalistic representation namely, modelling and perspective. Unlike his father, Jahangir (r.1605-27) took less interest in manuscript illustration and directed his painters to produce sumptuous albums (muraqqa) of paintings and calligraphy. Chosen masterpieces were mounted on folios with superbly illuminated borders (hasiya). Emperor's discerning patronage made the art of painting reach unprecedented level of perfection. There were outstanding painters like Ustad Mansur, who specialized in intimate studies of florae and faunae. Elaborate court scenes were based on observations and the painters never missed portraying the court musicians whose sole function was to enliven the royal ceremonies with appropriate music. Meticulously stippled and patiently blended translucent tonalities were burnished carefully and the painted folios resembled exquisitely enamelled plaque.

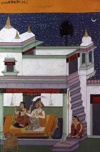

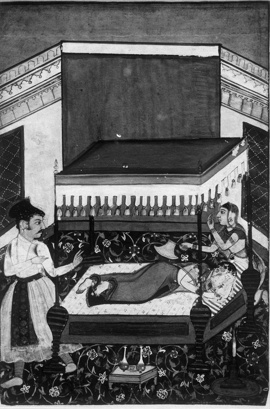

Shahjahan (r.1628-58), the builder of Tajmahal, inherited a flourishing atelier of remarkably talented painters who specialized in commemorative portraits and formalized depiction of the splendour of imperial ceremonies. On the other hand, sensitive portrayals of holy men and sufi saints against a backdrop of enigmatic chiaroscuro are openings into the zone of introspection. For Aurangazeb (r.1658-1707), painters and musicians were "workers of the devil". Though there are some fine portraits of his early years, the production of albums and illuminated manuscripts had virtually ceased. His puritanical orthodoxy led him to close down the imperial atelier and discontinue the musical performances; as a consequence the artists were left with the option to explore fresh patronage in the principalities of Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh and Deccan. Paintings commissioned by the later Mughals (1707-1858) offer an enchanting range of subjects that included musical evenings and dance performances in the seraglio, spiritless court scenes and mannerized portraits.

-

04 07

Provincial and

Deccani SchoolsIndian Miniature Painting Overview

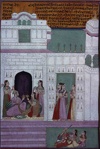

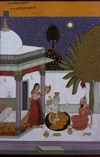

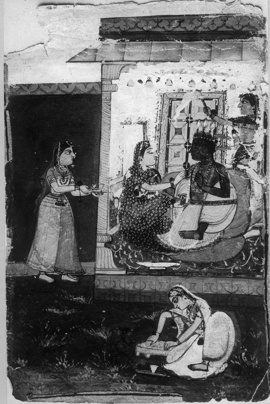

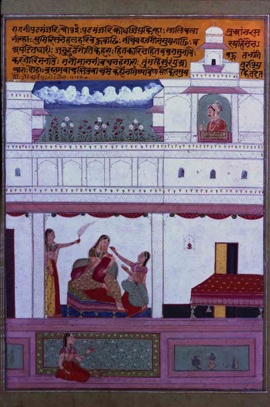

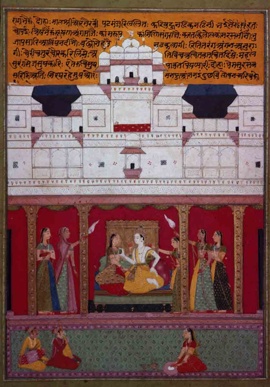

In the delightfully ornamental style of Murshidabad and Avadh (Faizabad and Lucknow) may one witness a fascinating afterglow of the Mughal pictorial idioms. The hereditary painters migrating to these centres with their stock of master drawings evolved a sumptuous technique, manifest in the generous use of metallic pigments, exotic decoration and a redundance of stippling for sheer tonal contrast. Musical evenings in the walled garden or on the terrace were set against a beaming post-monsoon sky of red and gold-enhanced clouds. Apart from portraits and court scenes the painters produced ragamala sets for an elite circle deeply immersed in music.

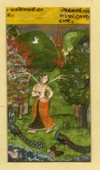

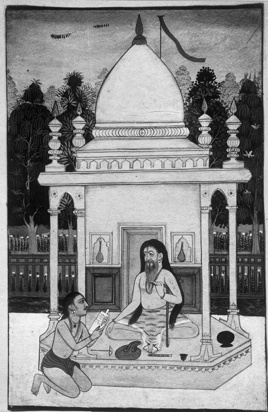

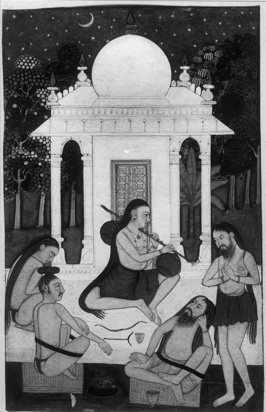

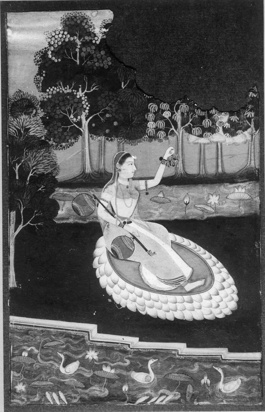

Miniatures (16th – 19th centuries) from the major Deccani centres namely, Ahmadnagar, Bijapur, Golconda and Hyderabad display a particular stylistic convention of overtly lyrical linearity and superbly gorgeous colour harmony. Naturalistic portraits are few. In comparison to the Mughal examples of court scenes and documentation of hunting episodes are less factual. However, there abound evocative picturization of ragamala and conceptualized rendetion of strang-looking yoginis and sufi mystics.

- 05 07

Rajasthani Schools

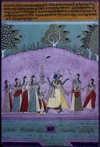

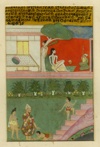

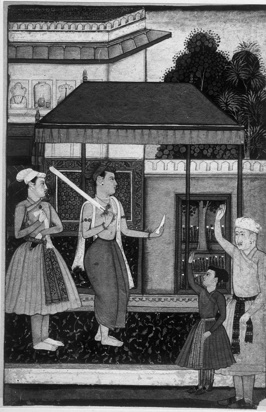

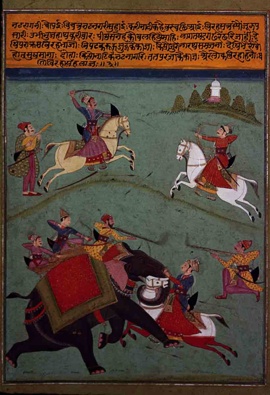

There flourished numerous schools of miniature painting in the principalities of Rajasthan between 17th and 19th centuries. In terms of expression and on the basis of inherited tradition there can be traced divergent styles. Mewar and Bundi-Kota, Jaipur, Kishangarh and Nathadvara in eastern Rajasthan and Jodhpur, Bikaner and Jaisalmer in the western desert-locked region became major centres. Painters who failed to measure up to the standard of excellence at the imperial atelier of the Mughals sought patronage of the Rajput kings. Incidentally, many of the rulers were scholars, poets and musicians. Moving from one centre to the other, painters facilitated a happy inter-fusion of stylistic idiosyncrasies. Apart from the Mughal and Deccani influence, the regional styles of folk painting did also make their dent. However, naturalistic depictions comparable to those by the Mughal masters are indeed few and far between. Rajasthani painters preferred to revert to types and motifs to strengthen the symbolic nuances of the theme. Vibrant primaries and decorative treatment of the florae enlivened the pastrol idyll. The two celebrated epics, Mahabharata and Ramayana, and a plethora of sacred and secular lores were used as thematic raw material.

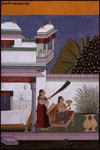

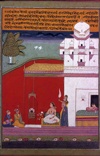

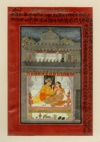

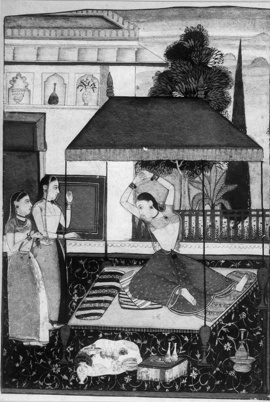

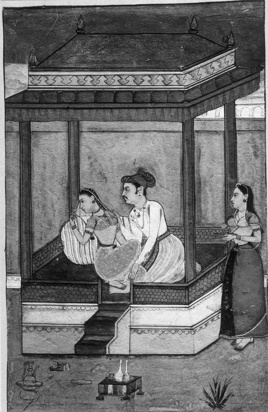

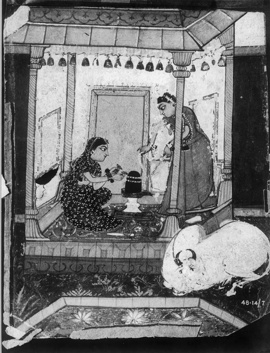

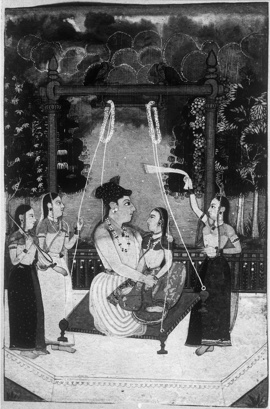

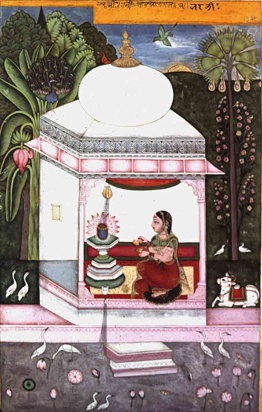

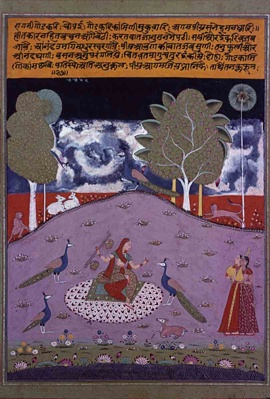

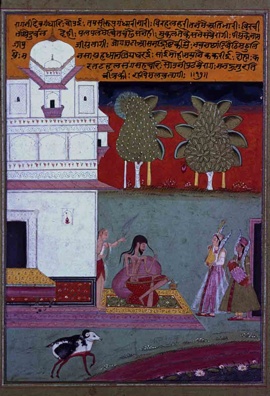

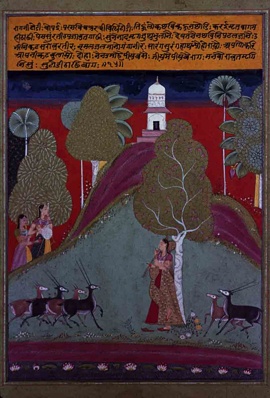

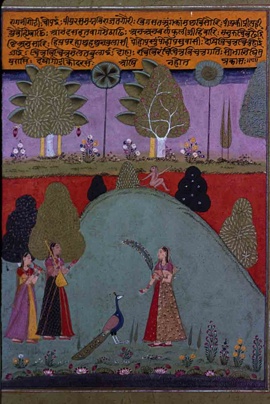

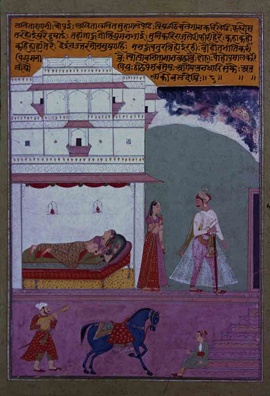

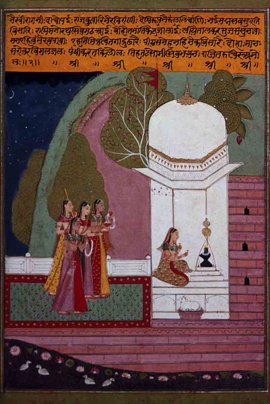

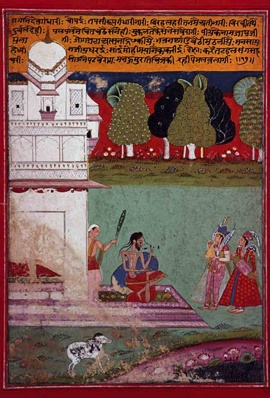

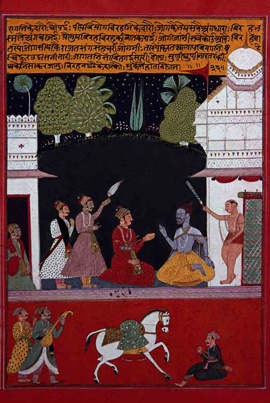

Medieval Hindi literature revolving around the sringara theme was indeed a persistent source of inspiration; in particular, Rasikapriya and Kavipriya of poet Keshva Dasa and Satsai of Behari. Sringara poetry described numerous emotional states of heroes (nayakas) and heroines (nayikas). And, such typecasting prompted the painters to go ahead with the visualization of each romantic situation with remarkable insight. Other closely related theme was barahmasa that narrated the cyclical changes of season and their impact on the lovers' attitude. Ragamala sets were exccuted according to the iconographic pattern prescribed for each raga and ragini and, almost in every example the Sanskrit or Hindi ragamala text was written over the upper margin alongwith a label for the particular musical mode. This practice would confirm the patrons' personalized involvement with these miniature series that enabled them to have a complete experience of the melodic mode through literary and visual.

Simultaneously, the painters were also entrusted with the task of recording the memorable musical soirees held in durbar and women's apartment. In many such paintings do we notice the inscribed portraits of leading vocalists and accompanying artists. We do also get considerable idea regarding their status in the court while gleaning through some of these candid portraits. Several schools of painting in central India, especially those of Malwa and Datia, demonstrate a crisp brushwork and a certain earthy gusto relatable to the pre-Mughal tradition and early Mewar-Bundi examples. Rajput families ruled the region and may well have commissioned sets of ragamala, sacred texts like Bhagavata Purana and Ramayana, as also sringara literature like Amaru Sataka and Rasikapriya. Dynamic stylization and bold patterning counterbalance flat colour fields of contrasting hues, of black and warm red, yellow and ashy grey.

-

06 07

PAHARHI SCHOOLS

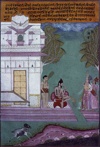

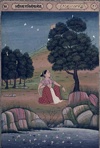

Artistically inclined Rajputs ruling over the Pahari states of the Himalayan region had their modest ateliers full of gifted painters. However, the tradition of painting tended to be short-lived primarily because of the frequently altering political and economic conditions. Conceptually sublime and technically superlative, the Pahari or the "montagnard" miniatures from the princedoms of Basohli, Guler-Kangra, Chamba, Jasrota and Garhwal are unanimously acclaimed landmarks of Indian painting. The earliest examples datable to the second quarter of the 17th century are from Basohli. Emigrant artists trained at the Mughal atelier of Lahore and Delhi were responsible for introducing Mughalized naturalism and a refined technique to the Guler painters in the second quarter of the 18th century. This new trend soon spread over other centres and, especially some of the exceptionally gifted painters of Pandit Seu family active at several princely ateliers played a key role in the dissemination of the idiom. To the precision of a Mughal-derived realism was added the nuances of the medieval devotional poetry and sacred Hindu lores.

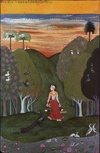

Figures endowed with great physical charm and expressive cadence were set in the backdrop of local landscape, that of hilly terrain and glades, rivulets and dense clusters of shady trees entwined with flowering creepers. "This magic world is not unreal or fanciful", rightly opined Ananda Coomararwamy," but a world of imagination and eternity visible to all who do not refuse to see with the transforming eyes of love" (Rajput Painting, 1916, p.7). Nainsukh (lit. "delight of the eye") the younger son of Pandit Seu, served Raja Balwant Singh of Jasrota and later Amrit Pal of Basohli. Most remarkable of Pahari masters, Nainsukh never failed in creating "an intensely, sympathetically observed world that seems still to breathe". He did wield considerable influence on the next generation of painters of the entire region inclusive of those trained at his family guild. In general, Pahari painters followed the ragamala system of Mesakarna, a sixteenth-century court priest of Rewa, central India. In his elaborate list, Mesakarna cited a visual and audio counterpart to each of the six ragas, thirty-one raginis and forty-nine raga-putras.

-

07 07

Wide range of media to explore

The Ragamala digital experience has been crafted to deliver a rich experience to the users across a wide array of media ranging from images to sound:

You are currently viewing:

Part 3: Indian Painting

View Part 4: Further Reading

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)