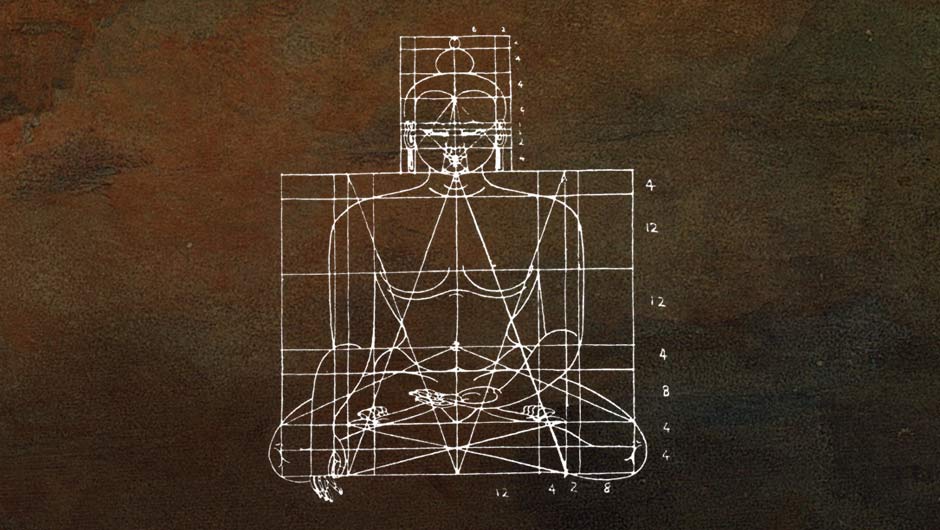

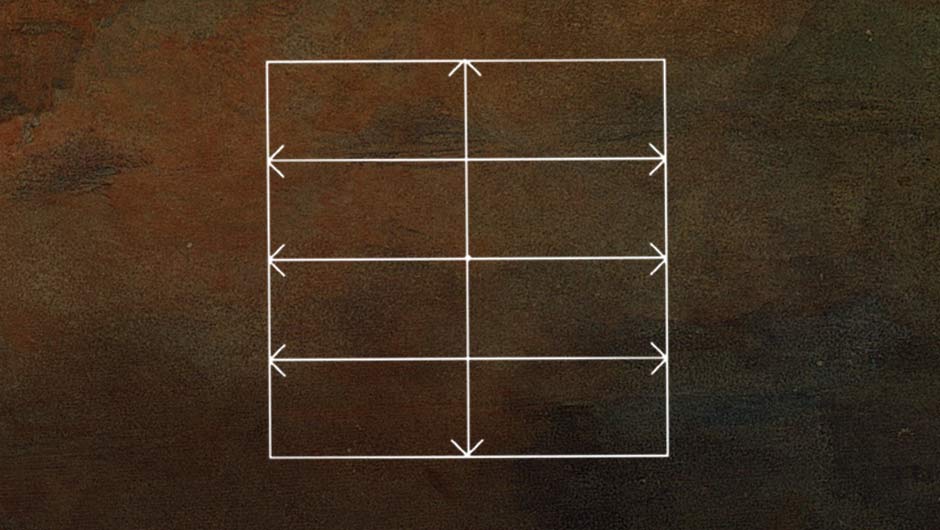

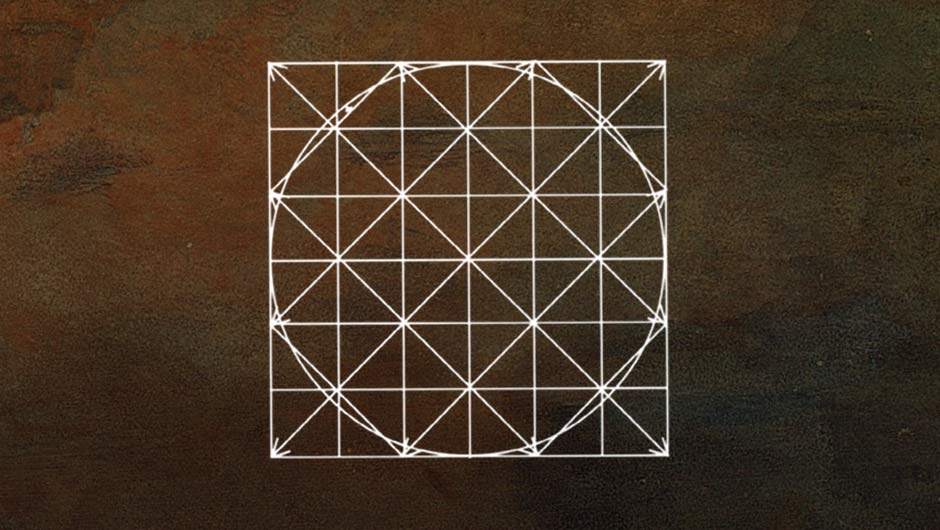

The anatomical infrastructure of the particular statue can first be studied as a unit based on the panjara, or orthogonal grid of vertical, horizontal, diagonal and depth dimensions. Interacting energy impulses operating within the panjara perpetually animate the image.

The following are the fundamental relationships of the vectors animating the grid:

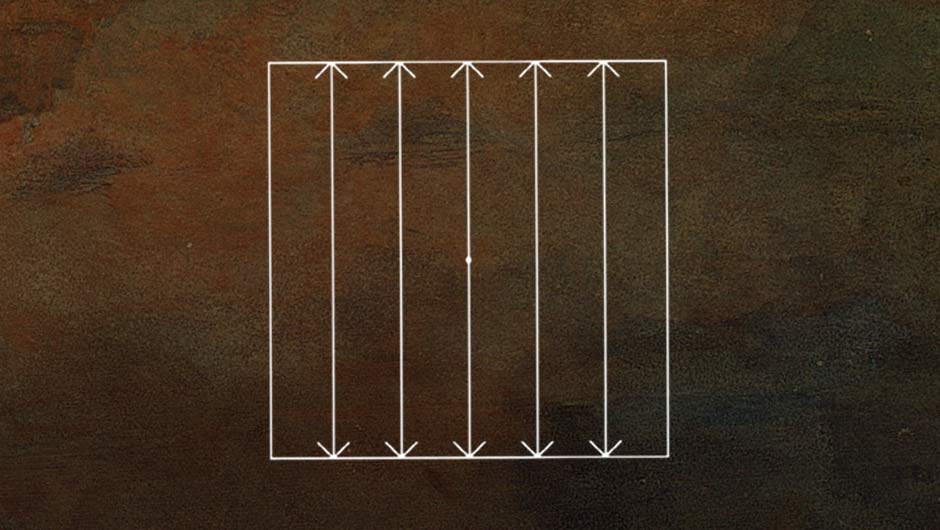

Vectors move upward and downward, but there is little disquiet.

Vertical and Horizontal: Equivalent energies emanate from more or less perfectly balanced vertically and horizontally stationed elements, causing a conflict when an effort is made to have the statue come to rest; this gives an impression of mobility.

Vertical and Horizontal: Equivalent energies emanate from more or less perfectly balanced vertically and horizontally stationed elements, causing a conflict when an effort is made to have the statue come to rest; this gives an impression of mobility.

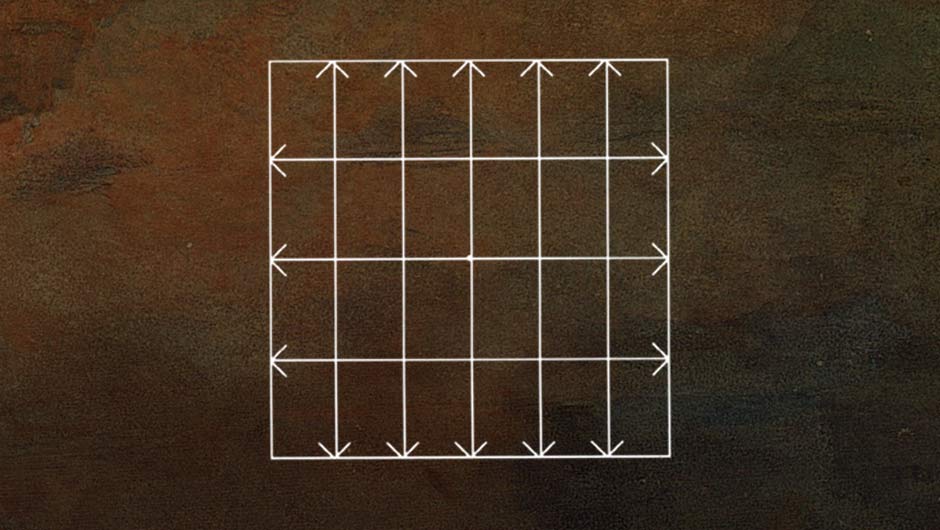

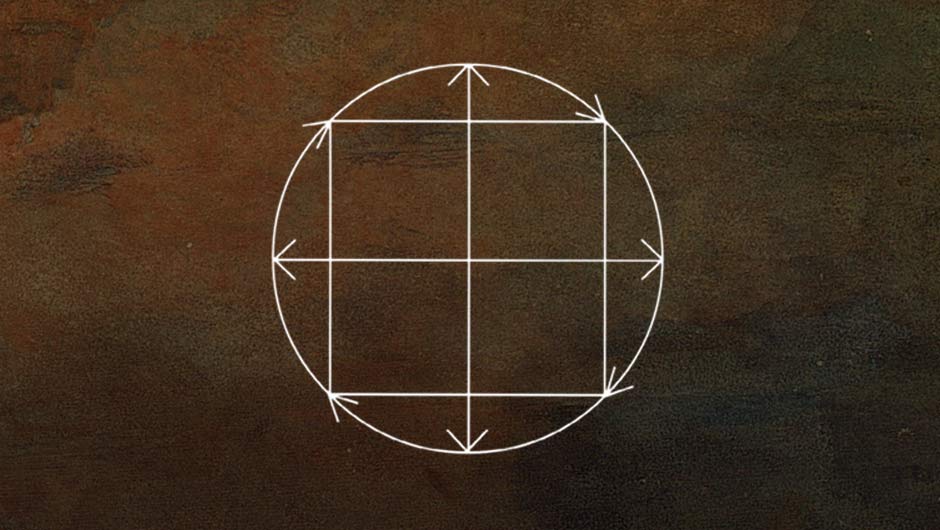

While there is no actual circumference, an immanent circularity is the major characteristic of the grid.

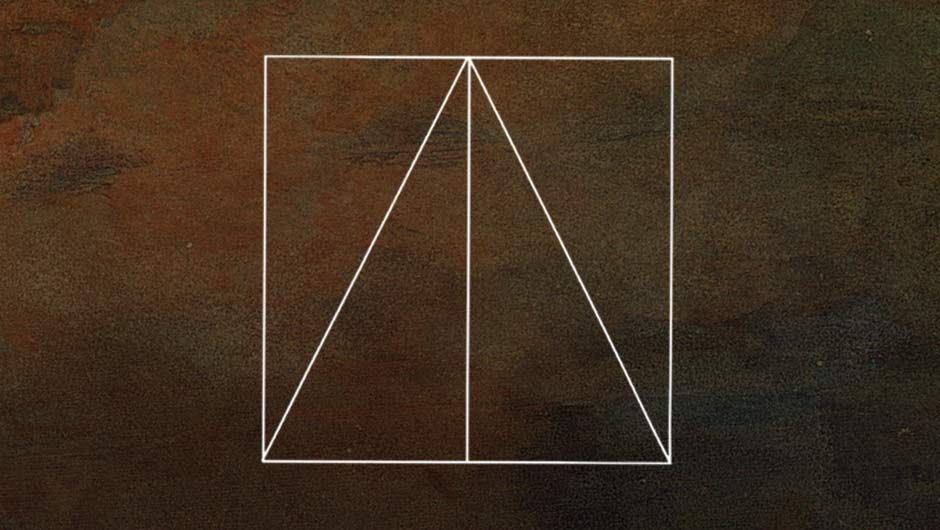

The grid is visibly triangular.

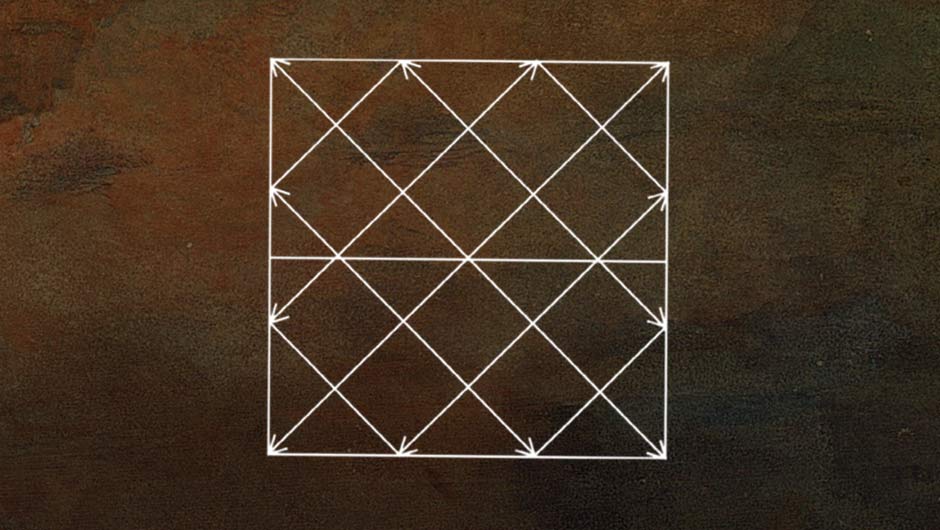

Vectors move diagonally across the field.

Vectors are integrated across the field.

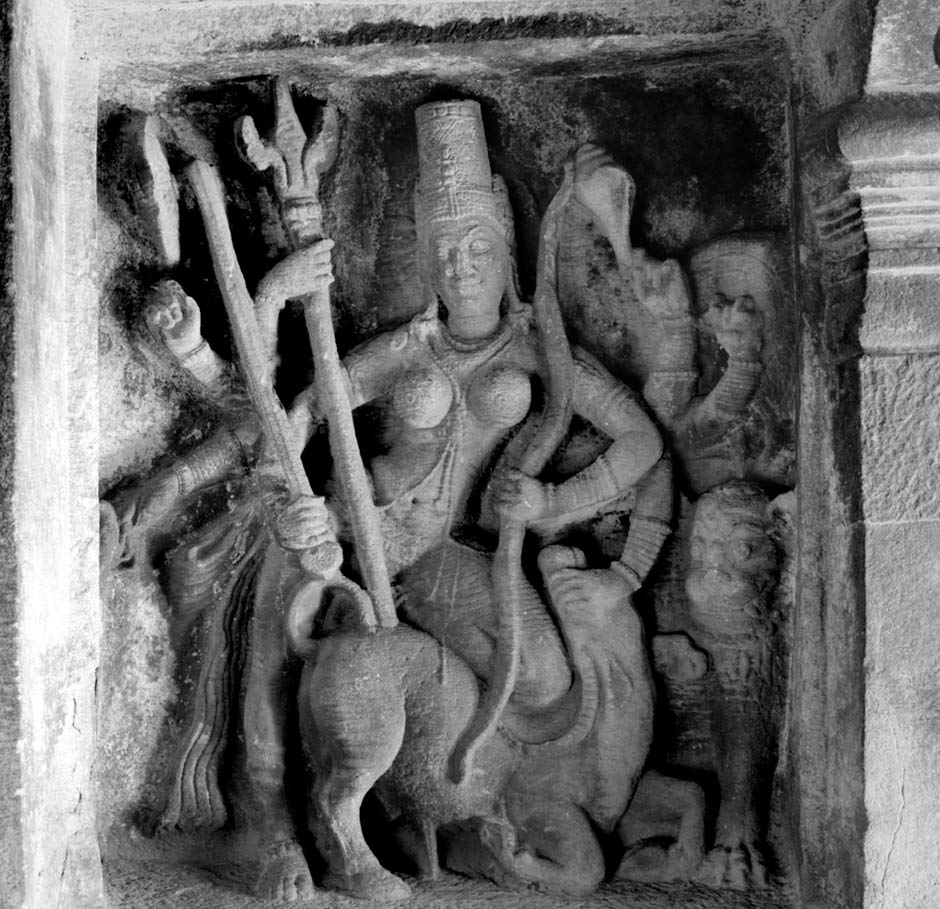

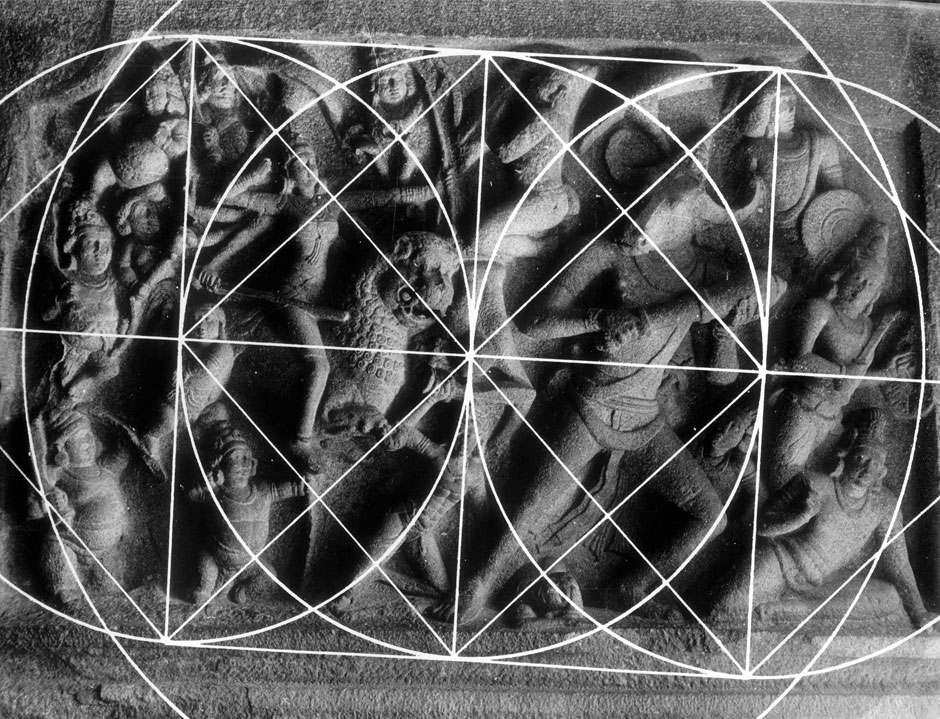

In this panel the goddess Durga on her lion, battling the buffalo Mahisa, is not a symbol about good defeating evil; that conception has been imposed on to the myth by western commentators. In the Indian context it may be understood as the conflict between two equivalent forces—nature's chaotic and dangerous vital energies. The narrative refers to the antagonists, each equally capable of love, violence, transformations, and all the opposites inherent in the human condition. As the spectators contemplate the meaning in the myth, instantaneous transformations seem to be in process: furious life forces are being portrayed. During the battle, as she quaffs her liquor, the goddess loses all control; she is wild and frenzied and so is her antagonist the buffalo. They are equals in a perpetual vicious struggle, and while Durga does indeed end the battle with his decapitation, like many other heroes of east and west, Mahisa soon is resurrected into life and sits at her side in heaven.

The designer sculptor confronts life's ambiguities by creating a symbolic structure outside of himself – the unifying work of art. During the creative process, the flat plane of the rock is transformed into a multiplicity of interacting volumetric shapes, imagining the activities of the dramatic personae of the story – the oppositions and correspondences inherent in the drama of the struggle. While the sculptor concentrates on carving techniques appropriate for achieving a similitude of the myth, simultaneously, in a parallel process, his ongoing brain activity produces an integral graphic image, very much outside of his conscious control. The shapes and forms of the carved rock then seem to be permeated with a fundamental unifying structure, an invisible, archetypal skeletal linear diagram. The inherent symbolic, mentally initiated mirror of the ongoing processes of the creative brain of the artist is automatically incorporated, undergridding and unifying the concrete, diverse sculpted forms. The grid is prior to the assembled forms and dominates them, but for the spectator, it can only become known – to be brought out from the deep recesses of the phyche – by concentrated focus on to the artwork.

The mental conception, the diagram (panjara), imposes order on to the dynamic forces of nature – on to the world's perpetual oppositions. It is the cage for the raging lion, the harness for the wild forces. But at the same time, mobility of life's processes is synchronized with the schematic framework. The diagram defines the contrapuntal oppositions and dynamic integration of the tumultuous life forces. Appearing universally in all periods and geographical locations in art works, the panjara is the ubiquitous yantra. Everything refers to and is ultimately controlled by the still, unchanging central point, (nabhi), out of which all life emerges and which draws in all the multiplicities back into itself. The circumference acts to contain the forces within, while at the same time, it receives energies from the centre. Vertical and horizontal axes, square and diagonal vectors, animate and energize simultaneously. In this panel, the head of the upside-down dead warrior forms the brahmasutra, the central vertical axis, while his spherical head, at the exact centre of the panel, is situated at the central point of the diagram.

When at the sites where he or she is in confrontation with the sculpture, the spectator might initiate a process of isolating the underlying grid, which, although unseen, will greatly animate and enhance the experience.